david coombe history

david coombe history

SUMMARY: November 1845 to February 1846 in Adelaide, South Australia was an intense period in which Daguerreotype photography was pioneered by George Heseltine, Robert Norman, S T Gill, Edward Schohl, Robert Hall and G B Goodman. There was also an earlier effort in August 1845 when William Little "acquired" Daguerreotype.

With the advantage of digitised newspapers, I examine this microhistory and reach different conclusions from previous writers.

I identify an earlier milestone which takes the history of photography in South Australia back another two years to August 1843.

I also suggest what became of the first Daguerreotype brought to Australia, to Sydney in 1841 by Captain Lucas of the French Oriental-Hydrographe expedition.

This article contains much detail (which is necessary for an analysis), but is also a narrative (which may interest more readers). It is about a 15 to 20 minutes read. The narrative shows us how hectic was the Daguerreotype summer of 1845-1846 and allows us to draw out something of the characters of the first Daguerreotypists.

Article type: NARRATIVE & ANALYSIS

In this article ...

NOTE: A select timeline with hyperlinks (below) contains much of the evidence behind this article. To reduce clutter in the body of this article, some references are not footnoted if they already appear in the timeline. You may wish to click to open the timeline in a separate window for handy access. (It is more of a reference appendix than a section to be read.)

Photography in Australia began as an indirect result of a failed French expedition.

In August 1839 Frenchman Daguerre's photographic invention – known as Daguerreotype – was made available to the world. The following month the French ship Oriental-Hydrographe left on a Naval training voyage "envisioned as the first voyage around the world to be documented through photographs, publicising the first commercialised process based on daguerreotypes across the continents." (Turazzi, 13) The Oriental-Hydrographe sank in June 1840. But much was salvaged and the ship's Captain Augustin Lucas made his way from Valparaiso to Sydney aboard the French trader Justine which was captained by his brother François. (Turazzi, 240) Lucas arrived in Sydney in March 1841 with a Daguerreotype. A fortnight later he offered his gear for sale, with training, through the store of Joubert and Murphy.

Captain Lucas, even after ordering a daguerreotype apparatus [from] Daguerre himself, learning how to operate it and demonstrating the novelty in the ports visited, sold his equipment when he arrived in Sydney because he was in financial trouble. But also, because he was a captain in the merchant navy, he did not intend to make a living with the daguerreotype and his plans were different. (Turazzi 2020, p.259)

A month later came the first newspaper report of a photograph being taken in Australia.

At the stores of Messrs Joubert and Murphy, an interesting trial of the advantages of the Daguerreotype was made on Thursday, at which we were present, and received the politest attention at the hands of the gentlemen who conducted the experiment. Our readers will be aware that this instrument is the recent invention of M. Daguerre, a Frenchman ... On the occasion we refer to, an astonishingly minute and beautiful sketch was taken of Bridge-street and part of George-street, as it appeared from the Fountain in Macquarie-place ...

Nearly two years later Joubert would offer a Daguerreotype for sale – this would have been the Oriental-Hydrographe apparatus – and timing suggests it may then have been taken to South Australia. (More on this to follow.)

The second Daguerreotype arrival in Australia, also in Sydney, was in late 1842 when George Barron Goodman set up a Daguerreotype business. I previously revealed the true identity of Goodman – Australia's first professional photographer. (More will be said about Goodman who also made a brief visit to South Australia.)

Our focus here is South Australia which has been thought to have only got Daguerreotype after (in order): New South Wales, Van Diemen's Land and Port Phillip. (This article will show Adelaide second after Sydney.)

Historians have generally taken one of two views as to who was South Australia's first professional photographer: the artist S T Gill or the instrument maker William Little. In The story of the camera in Australia (1955), Jack Cato writes (p. 170-1):

Samuel Thomas Gill was the first to import Dauguerreotype equipment from England to Adelaide, doing so direct from Beard of London, who was Daguerre's patent agent. Beard also sent out specimens of work done in London, and when Gill exhibited his own Daguerreotypes side by side with them in Adelaide, the author of the report says Gill's pictures far surpass them. S.T. Gill was Adelaide's first professional photographer, though it is doubtful if he did very much work because a few months after he imported his camera he went away with the ill-fated Horrocks' exploring expedition, and before he left he sold his camera to a young publican named Robert Hall.

Cato also acknowledges the prior effort of the instrument maker William Little, although without bestowing the professional photographer tag. South Australian photographic historian R J Noye in Dictionary of South Australian Photography 1845 - 1915 credited Little with "the earliest known photographic images made in South Australia". Previous Gill authorities have ignored Little.

The "professional" label is largely an arbitrary one when operations may have lasted just a matter of weeks. With the advantage of extra data points from digitised newspapers, I plot out a fresh story which is not so much a single beam but instead scattered rays of light; and I plot out an earlier story.

We turn first to the colonial arrival of two Daguerreotypists to be.

The barque Taglioni arrived in Adelaide from London in June 1844. Among the passengers were Robert Norman, a surgeon dentist, and George Heseltine, who appears to have been in search of a business. Eighteen months later they would be working together as Daguerreotypists though that business was clearly not their immediate intention. At once Norman established his dental surgery.

TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR, THE LADIES, AND GENTRY OF ADELAIDE.

MR NORMAN, Dentist, respectfully announces his arrival in the Colony from London, where he has practised as a Surgeon Dentist, for the last 18 years; during which period, he was fortunate to secure the patronage of the most able of the medical profession. Mr Norman trusts that, if the representation be correct, of the requisition of a first-rate Dentist in South Australia, he may meet with the encouragement the result of his system warrants. Every description of artificial, natural, and mineral teeth, from one to the entire set, fixed on the principle best suited to the case. Artificial palates, noses, &c.

Mr R. NORMAN, Surgeon Dentist, Wright street, Adelaide ...1

Within the year, in July 1845, Robert Norman moved to premises he had built for himself on King William Street. His two storey building was immediately captured by S T Gill in (his anachronistic representation of) Sturt's Overland Expedition leaving Adelaide, August 10th, 1844 (AGSA 0.644). Norman's building would later host a Daguerreotype, but not before the brilliant William Little had first "acquired" that "art".

It was August 1845. G B Goodman had just left Sydney and was taking his nomadic Daguerreotype business to Melbourne. Meanwhile in South Australia the newspapers reported William Little had a Daguerreotype of his own.

DAGUERROTYPE.–Mr W. Little, North Terrace, who has acquired considerable reputation as an ingenious mathematical and optical instrument maker, has just succeeded in acquiring the above important art. Thus parties who wish to send accurate likenesses to England, will probably be enabled to do so at a very trifling expense.

With clients encouraged at small expense to send their portraits "home" to England, this was clearly a commercial activity. But it was short lived; the next month Little was having supply chain trouble and changed from silvered plate (Daguerreotype process) to paper (Talbot's Calotype process). [Snippet blow includes original typo / spellings!]

PHOTOGRAPY.–A few weeks ago we noticed Mr Little's having succeeded with the daguerrotype. The difficulty of getting the requisite silvered plates in the colony presenting an obstacle to the bringing of this art into general use here, he has directed his attention to processes on paper.

We have just seen a few of Mr Little's specimens, from which it is evident how important this art will eventually become for the copying of plans, maps, drawings, engravings, &c. In an impression of a piece of lace, the smallest threads are distinctly marked, and the outlines well defined. The usual time for taking an impression is about ten minutes : the first impression is negative, consequently a second operation is requisite to bring out the shades in their natural order. In an experiment which we witnessed, a piece of white paper was transformed by the solar rays into a perfect picture in one minute. Mr Little has not yet tried portraits, but will probably do so soon ...

The report likely reflected standard Daguerreotype patter, such as that advertised by Goodman's former assistant John Flavell in Launceston: "... the sitting seldom exceeds ten seconds, and the whole is framed and delivered within ten minutes".

Did Little then succeed in portraits with Calotype and attract paying customers? We don't know and there are no further reports of his photography in the newspapers. The next we read of Little is five months later when he had constructed a reflecting telescope.2 In another five months he'd made an oxyhydrogen (illuminating) microscope and was charging 2/- admission for an evening demonstration.3

Where did Little get his Daguerreotype and where did it go?

Daguerreotype consisted of a camera obscura, plates, chemicals and a process. Those who "acquired" the Daguerreotype were likely buying a package. One such package – instrument, plates, chemicals and training – was for sale in Sydney on 16 July 18454 probably on behalf of Goodman who was leaving for Port Phillip. It was in time for Little, but given the absence between times of any ship to Adelaide this source can be ruled out.

When Little changed his process from Daguerreotype to Calotype, the constant was the camera. It's not stated definitively that he'd imported one. Clearly Little had the skills and resources to make optical instruments and possibly made his own camera, perhaps repurposing its lenses and mirrors for his later builds of telescope and microscope. (Cato (p.170) thinks Little made his own camera in Adelaide.)

Later we will reconsider the origin of Little's camera.

With Little seemingly abandoning photography and the travelling salesman G B Goodman still in Melbourne, Adelaide at this time was a Daguerreotype vacuum.

That may have changed on 15 October when the barque Augustus arrived in Adelaide from London. Included in the cargo was: 1 chest Heseldine (sic.); 1 case, 1 box, 1 cask, Norman; and 1 case, Hall. The consignees were almost certainly George Heseltine and Robert Norman and probably Robert Hall – all imminently to operate daguerreotype. Did the unspecified contents include apparatus? And would it have been Heseltine, Norman or Hall? Norman's consignment was the most interesting, but his profession as dentist surgeon may be sufficient explanation for that.

Although we cannot definitively say Augustus brought a daguerreotype, later events support this theory, in particular Heseltine's clarification he was the "sole proprietor" of the first "Norman and Heseltine" operation.

Late in 1845, S T Gill was completing an extensive commission for James Allen. Allen left for England on 27 November and in that same month The Register newspaper reported on Gill's use of a daguerreotype which had recently been imported into South Australia.

A daguerreotype has been sent to the colony, and is in the hands of Mr Gill, the artist. It appears to take likenesses as if by magic. The sitter is reflected in a piece of looking glass, and suddenly, without aid of brush or pencil, his reflection is "stamped" and "crystalised". That there should be an error is absolutely impossible. It is the man himself. The portrait is, in fact, a preserved looking-glass. We understand Mr Gill will soon be prepared to show us as we are, and beyond a doubt his wonderful machine will be "the glass of fashion and the mould of form."

(As an aside, the exuberant reporting is possibly that of J D Willshire, of whom we learn more in July 1846: 1846. The Camel, Horrocks's Expedition, Gill's Parting Supper and a Newspaper Reporter.)

Six weeks later, in time for Christmas, daguerreotype was first advertised in Adelaide.

DAGUERREOTYPE, AT MR NORMAN'S, KING WILLIAM-STREET.

LIKENESSES taken by this method, which insures at once a perfect and an unchangeable representation of the person sitting, not liable to be affected by any changes of atmosphere or climate, but presenting at all times as true a resemblance as a man sees of his own face when looking upon himself in a glass.

The artist is in possession of all the latest improvements of Sir John Herschell, Fox Talbot, Robert Hunt, Daguerre, Claudet, and other distinguished philosophers and men of science; and these being brought into action in a climate so favorable to their complete development as that offered by the sunny skies of South Australia, secure a likeness of extreme beauty and delicacy, in addition to the invaluable consideration of its being, not a creation of the painter's

fancy, but a veritable representation of the man himself.

N.B.–The artist may be seen as above every day from ten till four o'clock. The process is not confined to the taking of a single likeness. Dec. 22d, 1845.

The operation was at Robert Norman's. The "improvements" imply this was the latest daguerreotype from England. The advertisement was accompanied that day by editorial:

We had, yesterday, an opportunity of seeing a few portraits taken by the Daguerreotype process, and were much struck with the clearness, sharpness of outline, and striking correctness of the likenesses exhibited by this novel application of the arts ... we should think that the enterprising artist will meet with the patronage of every one who is desirous of handing down a correct likeness of himself or his friends to his family as a heirloom. There is one other great recommendation in this process, namely, that the whole time occupied in taking the likeness, as perfect as the reflection of a face in a mirror, does not exceed two minutes. The specimens we have seen, far surpass those of the patentee, Mr Beard, an effect which we suppose must in some degree, be attributed to the clearness and brightness of our atmosphere and sky.

Was "the enterprising artist" still Gill? At the time the term "artist" was broadly applied to most Daguerreotype operators, so we can't be sure this was Gill. A few days later another newspaper describes this operation as being managed by Norman and Heseltine.

Meanwhile in Melbourne (Port Phillip) Australia's travelling daguerreotypist, G B Goodman, was having trouble. Goodman had been incensed at the prospect of competition from a respected local. His reaction had triggered bad press. But Goodman's business model relied, at least in part, in the positive interplay of advertisements and advertorial and now he'd lost that in Melbourne. He left reportedly owing money to tradesmen and a newspaper.

A TREAT FOR ADELAIDE – A person named Goodman, who was keeping a Daguerrotype establishment in Melbourne, took his departure rather suddenly for Adelaide, leaving various accounts unpaid. This is too bad, as he received a great deal of money out of Melbourne. He owes the Gazette office an account for advertising, and on seeing the notice of his departure in Thursday's Herald, we sent our collector after him, but we only had the expense of the boat to pay, and he got clear off ; he owes this office between £5 and £6.

The departure from Melbourne of the barque Cleveland was delayed until 28 December and she reached Adelaide on 9 January 1846. Given the circumstances of Goodman's Melbourne departure, he may have not anticipated any line of credit and set up in Rundle Street at the residence of Emanuel Solomon. (It may be significant that Solomon, previously in business in Sydney, was a co-religionist of Goodman's Sydney father-in-law, Abraham Polack.)

Goodman's first advertisement was on 23 January. By then, he was facing competition from Norman, Heseltine, Schohl and Hall and after an ever so brief stay, on 5 February he announced his impending departure.

The summer of 1845-1846 was a flurry of Daguerreotype. Who were the players? We can dissect each of the operations and operators. Daguerreotype was a process; it was also consumables: glass plates, chemicals and morocco cases. The enduring component was the camera and through the hectic jockeying of business we can deduce with some confidence which equipment (English or French, Beard or Paris) was used by whom, thus:

(A more extensive timeline is below.)

It's unsurprising these early ventures struggled. Entrepreneurs had to create a demand for a brand new product using a process they themselves may yet to have mastered. The last advertisement for Schohl and Heseltine at Norman's appeared on 14 March 1846. Following this Robert Hall continued as the only Daguerreotype operator in Adelaide until he readied to leave for a visit to England in June 1849.

How can we consider these pioneers of photography?

It's interesting how many of these Daguerreotypists became publicans: Goodman, Heseltine, Hall. Despite his early domination of the Australian scene Goodman gave up photography in May 1847, Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer jesting:

CHANGE OF OCCUPATION.–A rumour is current about town, that Mr. GOODMAN is about to exchange the Daguereotype for the Drag-into-the-tap line.5

Robert Hall was the only one to continue long as a professional photographer.

If you've read this far, you may have the impression the early Daguerreotype business in Adelaide is now all historically wrapped up. But there is a big puzzle from more than two years earlier.

In August 1843 a poster caught the attention of eighteen year old William Anderson Cawthorne. It was in the window of a stationery shop – almost certainly that of Charles Platts'. It so affected Cawthorne he wrote a letter to the Register newspaper. (It was held over "under consideration" for more than a week before being published.)

THE FINE ARTS IN ADELAIDE.

Gentlemen–By giving publicity to the following, it will greatly oblige, Yours, W.A.C.

What would the people of England think of us, after reading the following notice, stuck up in the window of a respectable stationer in this town?–"Correct Likenesses taken in ten minutes.–Hall's Gallery, Currie-street, West end." Is it possible? they would exclaim.–Have they then actually got a Gallery of Portraits already?–and a West-end too?–Certainly the arts and sciences must be in a flourishing condition in Adelaide.–What shall we hear of next?

Might we not reply, with conscious pride at our elevated position with regard to scientific attainments, that balloons are constructing, and some even ready to start, either to Port Grey, or to the southern shores of the Gulf of Carpentaria, which bid fair to rival Henson's patent aerial steam carriage, and which promise to be reduced to purposes of practical utility quite as soon! Might we not also remind them of former projects in the Colony with respect to rail-roads, canals, and steam carriages, as affording proof of what South Australia has been so long, and so properly designated, namely, "The Land of Promise."

The "attainments" and "former projects", especially the cross-continental balloon, were yet to materialise. Cawthorne takes South Australia's moniker "Land of Promise" and seems to twist it to a land of promises unrealised. He appears to be mocking. So Cawthorne seems to be dismissive of the poster. But its content seems real enough, so what is it about?

Was there a sketch artist at Robert Hall's gallery? A paper silhouette cutter? Ten minutes was often the time stated to be needed for a Daguerreotype to be completed: sitting, developing and encasing. I think the most likely explanation is this was Robert Hall with Daguerreotype.

This evidence suggests Robert Hall in August 1843 was South Australia's first advertising photographer.

From where might Hall have got his apparatus? In Sydney D N Joubert was preparing to return to Europe and auctioned his household effects on 23 March 1843. Included was "a very superior DAGUERREOTYPE, complete, with all the Apparatus, and a great number of Plates". Joubert had the Oriental-Hydrographe daguerreotype – the first known in Australia. Three days after the auction Joubert and his family sailed from Sydney for London. That same day another vessel left Sydney – the brig Dorset for Adelaide with merchandise and five passengers, one of them by the name of Hall.

This is circumstantial evidence to be sure, but there is a good possibility that Robert Hall bought the Joubert / Oriental-Hydrographe daguerreotype in Sydney (where Goodman was still operating) and brought it to Adelaide.

(As an aside, Joubert visited Adelaide in March 1842 in his role as owner of the confiscated French trader Ville de Bordeaux but there is no evidence of him bringing his daguerreotype.)

Had Hall been relatively successful with the daguerreotype he would've surely got attention from the papers. Hall didn't then become a daguerreotypist, but instead continued as an ornithologist, animal collector and taxidermist. Perhaps he passed his daguerreotype on to William Little. Hall's Sydney purchase would also help explain why Little suffered from a shortage of plates, something he wouldn't have expected from a package deal.

The likely / possible provenance of the Oriental-Hydrographe daguerreotype (left France September 1839) is: Captain Lucas (1839-1841) → D N Joubert (1841-1843) → Robert Hall (1843-?) → William Little (? 1845).

It's extraordinary to think Hall's early role may have remained undiscovered were it not for a teenager's sarcastic letter.

Of all the Daguerreotypists in Adelaide in that intense period from November 1845 to February 1846, Robert Hall was the one who lasted. He exhibited Daguerreotypes in the February 1847 Exhibition of Pictures6:

And other than gaps for two return visits to England and a couple of stints as a publican, Hall continued as a photographer until his death in 1866.

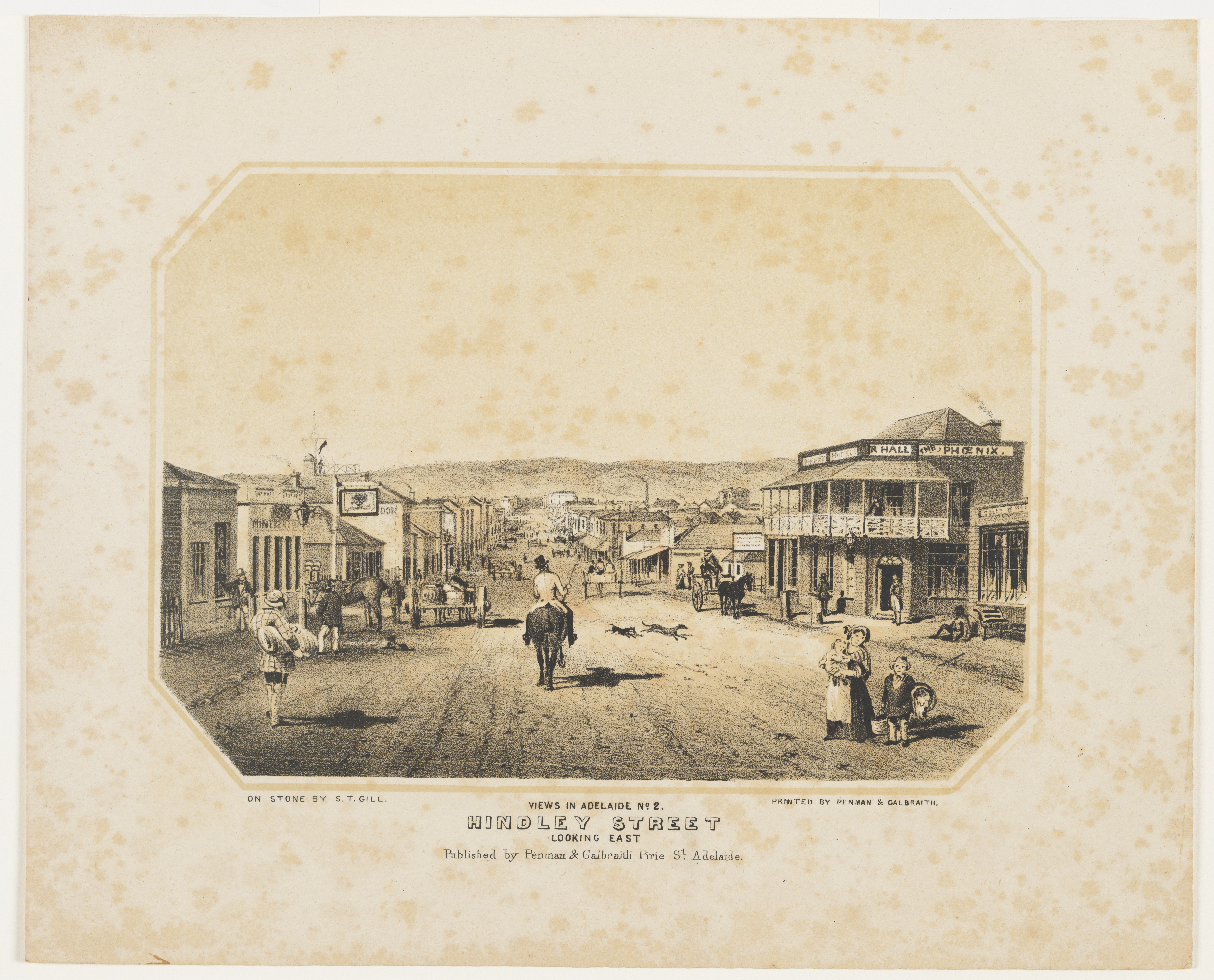

Views in Adelaide, no. 2: Hindley Street looking east | Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales DL Pd 260

Views in Adelaide, no. 2: Hindley Street looking east | Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales DL Pd 260

Left: This lithograph print by S T Gill in 1851 seems to show Robert Hall on the balcony of his Phoenix Hotel.

From November 1845 to February 1846 Daguerreotype activity in Adelaide was frantic: Heseltine, Norman, Gill, Schohl, Hall and Goodman. And a few months earlier was Little. Now we see Hall beat Little by two years and we can re-evaluate all their contributions and reassess their rankings. Gill can be demoted and I think Robert Hall can be promoted to the top of the ladder as the South Australia's premier pioneering photographer.

Previous Gill authorities have made much of Gill's pioneering use of the Daguerreotype.

Bowden (1971, 9): "Gill, who was living in Rundle Street, was Adelaide's first professional photographer, although he did not continue with photography for very long. The South Australian Register states he was the first to import Daguerreotype equipment from England. Gill's photographs were thought to have been better than those of Beard of London, who was agent for Daguerre's Patent. Shortly afterwards Gill sold his equipment to a young publican named Robert Hall ...".

Dutton (1981, 8): "In fact, Gill was one of Adelaide's earliest professional photographers, possibly the first; he imported daguerreotype equipment from England and produced some photographs of the highest quality."

Noye (Dictionary) about the 1990s:

Although it may have been Gill's intention to provide daguerreotype portraits, it is likely he failed to master the complicated process, and his camera may have been the instrument Norman & Heseltine used when they opened their studio in King William Street, Adelaide, on 22 December 1845. Their partnership was shortlived, and by the end of February 1846 Heseltine had joined with Edward Schohl, who had brought his own daguerreotype apparatus from Germany, and as Gill's camera would have become surplus it could have become the one 'lately imported from Paris' that Robert Hall bought in April 1846. (Noye, Dictionary, p. 131)

Grishin (2015, 58) posed the question in a chapter title: "Was S T Gill South Australia's first photographer?", but reached no conclusion. A close reading suggests Grishin was unsure of previous claims.

This article moderates the view of Gill's role.

However, photography did play some role in Gill's work. Around 1850 he made several portraits based on photographs – see S.T. Gill, March 1850 to March 1851.

And in Sydney in 1859 Gill was planning to take a panoramic view from Government House.

Mr. Gill, well known here as an artist of considerable merit, and a very clever caricaturist, has obtained from the Governor-General the use of the lofty roost constructed in the domain for the photographic views taken by Messrs. Freeman Brothers, and intends to take from thence a panoramic picture of Sydney.7

Gill's panorama has not been mentioned by previous authorities and is as yet unidentified.

A reference timeline of significant events relating to this article. Events are in Adelaide unless otherwise described. Links are to digitised newspaper articles and you may want to search within the article to find the relevant text.

Cato, Jack, 1889-1971. The story of the camera in Australia / by Jack Cato, Georgian House Melbourne 1955

Turazzi, Maria Inez, 'The Oriental-Hydrographe and Photography - The First Expedition Around the World with an 'Art Available to All'', Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo, published 17 September 2020, accessed January 2024. <https://issuu.com/cmdf/docs/l_oriental-ingle_s>

Noye, R.J., 'Photohistory SA' (website), published 1998, archived by the Art Gallery of South Australia (9 September 2005), <https://noye.agsa.sa.gov.au/>

Noye, R.J., 'Dictionary of South Australian Photography 1845 - 1915", Art Gallery of South Australia 2007; accessed 29 October 2016 from <http://www.sapf.org.au/wordpress/upload/Dictionary%20of%20South%20Australian%20photography.pdf> (no longer available)

Robinson, Julie, 1963- and Zagala, Maria and Noye, Robert J. (Robert James). Dictionary of South Australian photography, 1845-1915 and Art Gallery of South Australia. A century in focus : South Australian photography, 1840s-1940s / Julie Robinson ; assisted by Maria Zagala Art Gallery of South Australia Adelaide 2007

David Coombe. Original 22 January 2024. Updated 2024-01-22. Formatted 2025-08-16. | text copyright (except where indicated)

CITE THIS: David Coombe, 2024, Daguerreotype and Early Photography, accessed dd mmm yyyy, <https://coombe.id.au/1840s_South_Australia/Daguerreotype_and_Early_Photography.htm>